How a draft night trade with the Celtics could make sense for the Knicks

Looking back — as a now proud NBA junkie, thoroughly Knickotine dependent — growing up across the pond in the United Kingdom in the 1990s was like growing up in a desert. Nothing but sand and sky and soccer. Back then, NBA content was to be cherished as a rare and precious keyhole into a miraculous other land. For an 11-year-old British kid at the turn of the century, the NBA was Narnia. It was Atlantis. It was Slam magazine sporadically appearing on shelves in your local newsagents. It was finessing your way to a 1 a.m. viewing of one hour of hoops, once a week, on one channel — if you were lucky.

One of the better Christmas presents I was ever given as a youngster was a VHS tape (google it, kiddos) called NBA 2000: Stars for the New Millennium. Its contents glowed like a package in Pulp Fiction, 50 glorious minutes of NBA highlights and profiles, with a smooth cosmic baritone voiceover which made anything sound possible. It had quite the lineup, featuring Kevin Garnett, Kobe Bryant, Penny Hardaway, Jason Kidd, Allen Iverson, Stephen Marbury, Damon Stoudemire, Chris Webber, Juwan Howard, Grant Hill, and Vin Baker. I watched that tape hundreds of times, and for a long time, those 50 minutes and 11 stars were my entire NBA universe.

That’s why, this week, when I stumbled on Vin Baker’s name, it struck a nostalgic note. Baker was selected with the No. 8 pick in the 1993 NBA Draft, and was the last No. 8 pick — 26 drafts ago — to make an All-Star team. For the Knicks, who have the No. 8 pick in the upcoming NBA draft, Baker as a best case scenario is a cautionary tale, evidence of the sobering reality that picking eighth very rarely turns into more than a player who is “just a guy” in the NBA.

No. 8 picks since 2010

Last decade’s eighth picks underscore this point nicely, which is relevant to how the Knicks should weigh the possibility of trading back on Nov. 18. The Boston Celtics, reportedly lusting after Onyeka Okongwu, are apparently open to swapping their three first-rounders (14, 26, 30) for a top-10 pick. The discussion about trading back for this deal, or something similar, hinges primarily on the relative value of picks at various points in the draft.

The 14th pick, at a glance, looks like it’s been at least as productive as the eighth pick over the years. The last All-Star taken 14th was Bam Adebayo, drafted in 2017, who made his first All-Star squad just last season. Prior to Bam though, you have to go back to the 1996 draft and Peja Stojakovic to find an eventual All-Star taken with the last spot in the lottery. Again, the overwhelming likelihood is that the 14th pick turns into “just a guy,” as last decade’s drafts demonstrate.

No. 14 picks since 2010

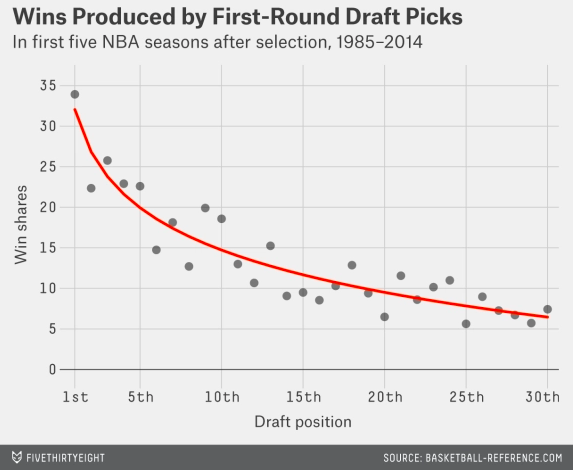

Lots of research (much of which is summarized by Tony El Habr here) has been done into the relative value of draft picks, and although the overall findings are generally uncontroversial, essentially confirming the no-shit principle that higher picks have a a higher expected return than lower picks, there are details that should inform the particular type of decision the Knicks find themselves facing now. Here’s a graph plotting the expected value of picks in the first round, one through 30, for the first five years of players’ careers, from a piece a few years ago by Nate Silver at FiveThirtyEight:

The correlation between draft position and expected value is non-linear, meaning the difference in expected value from the first pick to the fifth pick is greater than the difference from the fifth pick to the 10th pick. Draft position gets less and less valuable the deeper into the draft we go.

Let’s take this hypothetical Celtics trade as an example, with the Knicks swapping the eighth pick for the 14th, 26th, and 30th picks. We can use another table from Silver’s article, which puts a dollar productivity valuation on each first round pick, to better quantify the deal:

So the Celtics’ package of 14 ($11.9m), 26 ($8.35m), and 30 ($7.3m) totals $27.55m in cumulative value, $11.65m more than the $15.9m the eighth pick brings on its own. Granted, this is a crude cumulative calculation, which does not take into account the specifics of the Knicks’ context, nor the circumstances of the 2020 draft. But it does demonstrate that the difference between the eighth and 14th picks is significantly less, generally speaking, than a simple “six spots worse” calculation suggests.

It’s also worth noting that both the wins produced graph and the net profit table above are based on the rookie contract production of all players drafted in the first round between 1985 and 2014. Importantly, this does not take into account what can happen to a player long term — after their team-controlled rookie contract, where things get a little more complicated. The possibility of a player leaving via trade, or free agency, or simply getting injured, dilute the chances of future projected productivity occurring for the team that drafted a player, or occurring at all.

As Silver puts it:

“After winning the draft lottery, a team essentially needs to get lucky three times over in order to have a storybook ending. First, it has to draft the right player. Next, it has to convince him to stay in town. Finally, he has to play up to his new contract. The odds are that something will go wrong.”

For the Knicks, this is the bites at the apple argument of trading down. Trading the No. 8 pick for three lower picks that are nominally but not substantively less valuable, has the added benefit of spreading the risk of one player having to get lucky three times, to one of three players getting lucky three times. More bites at more apples.

So, in a clean and tidy vacuum, the Celtics trade makes sense. Of course, we’re not in a vacuum. We’re staring down the barrel of a messy draft, for a messy franchise, in a messy year; and each of these variables muddy the decision-making waters some.

Variable No. 1: The messy draft

All of the above about relative pick value and bites at the Vin Baker-shaped apple are nice, fluffy theory until you apply it to an actual draft, and the uncertainty in this draft creates some caveats to neat in-a-vacuum decision making. Of course, the Knicks have a draft board, and if there is a player available at eight who they feel is significantly better than the next-best tier of prospects on the board, you take that player and call it a night. For me, the two players who I’d take at eight are Isaac Okoro and Killian Hayes, in that order. Everyone has different wish lists — some have Hayes higher, some Okoro lower — and that’s what makes this draft so wild.

Bottom line, though: whoever the Knicks have in that tier, after all Walt Perrin’s draft prep, should be the pick if possible. If, however, that tier is off the board, and we’re left with the following six, in some order: Okongwu (who needs to be there for any of this to be relevant), Devin Vassell, Tyrese Haliburton, Kira Lewis Jr., Tyrese Maxey, and Pat Williams; then I’m looking to trade back, knowing one of these five will likely be there at 14.

Depending on the Knicks’ board, and how the first seven picks pan out on the night, this exact possibility is unlikely. But it’s a possibility — among many possibilities — that Leon Rose and company should have prepped for, and be ready to exploit come Nov. 18. The foreseeable variability of this specific draft means it’s highly likely that the draft boards of the seven teams picking ahead of the Knicks are in places significantly different to the Knicks’ board. This is a good thing. It increases the chances of a guy higher than 14 on Rose and Perrin’s wish list being available at the Celtics spot. On draft night, top-10 flux is the Knicks’ friend.

Variable No.2: The messy franchise

By messy franchise, I mean young franchise. The knee-jerk critique of the Celtics swap centers around the fact that the Knicks would have five picks in this draft if they made that deal; 14, 26, 27, 30 and 38. Meaning five rookies heading into a fast-tracked training camp with a roster already brimming with a bunch of young guys. This would be, as many have argued, very dumb.

This isn’t a reason to not do the Celtics trade, though. It’s a reason not to only do the Celtics trade. Leon Rose can reduce the number of young players on the roster, and maybe already has plans to move on from one or more of Dennis Smith Jr., Frank Ntilikina, or Kevin Knox. He can also consolidate two or more of the later four picks into a higher pick, in theory, provided the appetite from teams in the late teens or early 20s is there.

ESPN’s draft guru Fran Fraschilla said recently that, “In this draft, there’s no difference between 20 and 40,’’ lending itself to the likelihood that a team will be interested in a two-for-one swap, should Rose have his heart set on a Desmond Bane, Cole Anthony, or Aleksej Pokuševski; who all project to go around the 20-ish pick mark. The Knicks can preemptively do this before draft night using 27 and 38, which they have now, or Rose can line up deals to pull the trigger on if and when the Celtics deal goes through, using some combination of 26, 27, 30, and 38.

He can also draft and stash one or more of these picks on international prospects, keeping assets offshore, and having the same number of rookies — three — that would have been in training camp without the Celtics trade. Leandro Bolmaro, a 6-foot-8 playmaking wing from Argentina, and Yam Madar, a flashy 19-year-old point guard from Israel, are two promising overseas players who are mocked to be available in the late-first, early-second round.

The combination of these three areas of roster wiggle room — the kids on the current roster, the consolidation of picks, and the draft and stash route — make the “five picks is too many picks” argument less convincing. Hell, if we’re feeling really crazy, we could even utilize the G League beyond using it as some kind of naughty step for draft busts in waiting. Unfortunately, given the worrying trend of the pandemic, using the G League as a developmental creche this coming season isn’t as viable an option as it would usually be, in pre-plague times.

Variable No. 3: The messy year

Speaking of the pandemic, this year has been about as fun as a balloon full of vomit. Do we really want to cap it off by helping the Celtics get potentially the best player in this draft — Okongwu — with the eighth pick?

No, in an ideal world, we don’t. But this is not an ideal world. Leon Rose’s New York Knicks, who reportedly value the perception of improvement and long term flexibility above all else heading into the 2020-21 season, cannot make decisions based on how it may or may not benefit the Boston Celtics, however knuckle-whitening the disconnect between Danny Ainge’s team-building reality and reputation may be.

The only teams future Rose should be thinking about on draft night are his own. Should he have his sights set on a loftier haul than the Celtics’ late first rounders in this years draft? Absolutely! 2021 draft picks are more valuable than 2020 draft picks, both because of the quality of next year’s college crop, and because assets down the road give the Knicks more flexibility in the future. But extra assets today are better than no extra assets tomorrow.

Only Leon Rose — with all the information on all the variables, on the phone to Ainge on draft night, carefully calculating the blood pressure and perspiration rate of a (hopefully) very desperate Danny — can decide how hard to squeeze the Celtics. Should he go into the negotiation with the mindset to make Ainge squirm as much as possible, with the knowledge that the Washington Wizards, picking one spot later, will happily snap Okongwu up if the Celtics GM can’t get a deal done with the Knicks? One hundred percent yes. But he should be on the phone.

The eighth pick is better than the 14th pick, but the difference is much less than the difference between the first pick and the second pick, and only slightly more than the difference between the second pick and the third pick. By the time you get to eight, as nostalgic memories of grainy VHS Vin Baker remind us, you’re choosing from a pool of players likely destined for NBA anonymity. Good outcomes are Kentavious Caldwell-Pope and Terrence Ross and — yes, I’m afraid, maybe — Frank Ntilikina. These are NBA plumbers and postal workers and painters. Useful players, admirable servants to their NBA professions, but probably not the sparkling capital-S Stars of the next decade.

If enabling Ainge and the Celtics is a byproduct of making the Knicks’ war chest of assets a little heavier, then so be it. If, five years down the line, the Knicks are playing the Celtics in the playoffs, Mitchell Robinson and Okongwu are squaring off in the paint, two titans of the long-extinct center position, RJ Barrett is snarling at an All-NBA Jayson Tatum and his meticulously manicured mutton chops, we’re all cursing the draft night deal that dropped the missing piece into Boston’s lap, and we’re up close and personal with a disgusting Celtics dynasty… then the next five years have gone pretty damn well for the Knicks, to be honest.

Right now that scene feels as far away and mythical as the NBA did to an 11-year-old British kid pondering how many MVPs Grant Hill would win. We can only dream of the visceral hate we’d feel playing that hypothetical Celtics team in that hypothetical Celtics series. It would be beautiful, that hate, and if Leon Rose has to gift wrap Onyeka Okongwu for us to inch closer to feeling that cathartic cocktail of regret, of envy, of tribal desire again (finally)… he should do it.

Besides, they can draft Okongwu with the eighth pick, that’s the easy bit. They’ve still got to keep him happy and healthy and in a Celtics uniform, which history tells us is easier said than done. Look on the bright side, at least we won’t have to listen to every national play-by-play broadcaster simultaneously espouse the virtues of All-NBA-Little-Things big man Daniel Theis, while at the same time declare the Celtics thoroughly outmatched in the paint and in desperate need of an upgrade at center to the tune of rationalizing Enes Kanter’s existence. Give me a break.

See how calm and measured Knicks fans can be about the Celtics? We’re ready, Leon. If all the bobbing and weaving variables align on draft night, do it: flick over the first domino of down-the-road hate. There’s a world in which it makes perfect sense.