The Knicks’ defense: Good?

The deepest of deep dives into the hows and whys of what makes the Knicks D tick

The Knicks are . . . good at defense?

You’ve likely heard it on game broadcasts, NBA-crazed parts of the internet and maybe even from reporters dedicated to writing about the Knicks. What you probably haven’t heard from those reporters is an exploration of why the Knicks seem to have undergone a transformation from the 19th-ranked defense last year (by defensive rating, or DRTG for short) to fifth this year, sporting a DRTG of 109.5 (most stats included herein are through Sunday's Suns game).The last time the Knicks were good at defense was the 2020-21 season, when they sported a 107.8 DRTG. That defense was stout thanks to the explosive rim protection of Mitchell Robinson and Nerlens Noel plus solid perimeter defense from the rest of the Knicks, like RJ Barrett, Reggie Bullock, the much-maligned Elfrid Payton (sometimes) and ageless wonder Taj Gibson. This was back when Nerlens had knees and Mitch was a 210-pound spring who could dunk from the free throw line and block 3-pointers. They were a force in the paint.This season is different. The DRTG may be great but New York's collective defense around the rim has been lackluster if you go by the stats. As of Thanksgiving, the Knicks have allowed 65% of shots to drop within 6 feet, per nba.com, sixth-worst. These numbers are even more bizarre when you consider the historical success of the two-headed center tandem defending the rim. Both Mitch and Isaiah Hartenstein have long anchored solid defenses, regularly posting stout numbers in the mid- or low-50s in defensive field goal percentage allowed near the rim. Indeed, last year both were admirable rim protectors, yet the Knicks' collective team defense was still weak due to multiple very, very bad defenders getting significant minutes all year long, e.g. Barrett, Jalen Brunson and Julius Randle. Honorable mention also goes to Evan Fournier and Derrick Rose for tons of bad defense minutes in the first quarter of the season.So that’s the headline: team employing two great rim protectors has been crappy at rim protection, still somehow great at defense. Elite defense without elite rim protection is not completely unheard of (the Butler/Bam Miami Heat have long been the standard in this respect), but it is still surprising, and definitely weird.So how does this new Knick defense work? First let’s see what we can glean from stats, then we'll jump to video to study the "how" of this new Thibs defense. PART I: THE STATS

Into the numbers! A quick note: you’ll notice that I focus entirely on shot frequency, shot locations, FGA per game, etc., rather than efficiency at any given spot. I think right now there’s a ton of noise in defensive FG% at pretty much any location. It is pretty early in the season to gain insight from opponent’s 3P%; besides, I’m much more interested in the shot diet the Knicks are allowing. Speaking of:

Shots allowed close to the hoop

Per Synergy, last year the Knicks allowed the 2nd fewest shots around the rim at 27.6 per game.This year, that figure is even smaller: a league-low 26 per game. The next lowest team, Chicago, is at 28.If you go by percentage of possessions – which takes out the pace factor – the Knicks are still tops in the league at 32.1% of possessions at the rim.Conversely, the Knicks have forced opponents to take jumpers on 57% of their total shots, second-best in the league. Yes, that includes threes, and that is worth discussing.

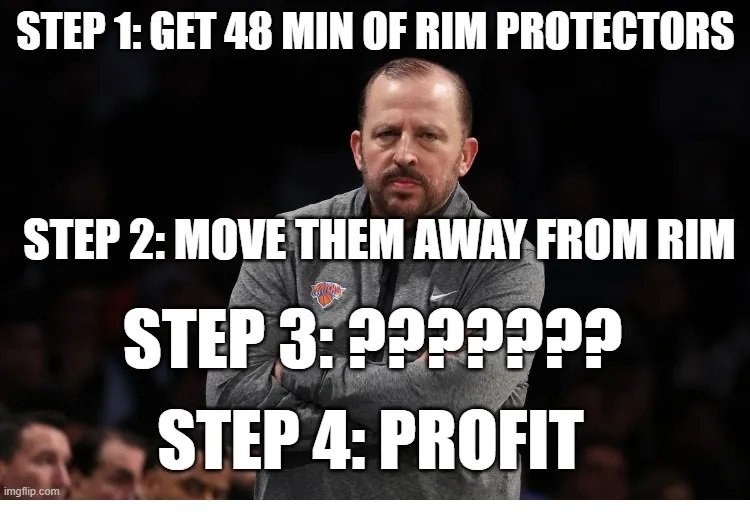

We'll return to this later, but rather than play exclusively drop defense and invite defenders to blow by crappy perimeter defenders and challenge our centers, Thibs is trying something different this year in the name of preventing those easy shots at the rim. You all remember that defense last year – 48 minutes of mostly drop coverage, matador point-of-attack defense and off-ball defenders over-helping to pack the paint, leaving 3-point shooters open, hence the crappy overall defense, a great segue to the next topic:3-pointers allowed

Last year the Knicks allowed 36.5 threes per game, fourth-most.This year? 35.1 allowed. Only a difference of about 1.5 threes, but that’s good for 17th-most in the league. Remember, comparing offensive stats across years is like comparing the price of food across years. Gotta account for inflation, the league chucking more every year and getting more creative on offense every year. The Knicks in 2023 are doing a decent job limiting threes, although we all know they can do better.

Synergy allows us to get a bit more granular. Last year they allowed 14.4 unguarded catch-and-shoot threes per game, a top-10 mark. This year? Down to 12.7 per game, almost top-10 again. A remarkable improvement, if it holds.Threes allowed is a pretty volatile stat early on in the season, and is also impacted by pace: if you slow the game down and allow fewer total possessions, you may allow your opponent fewer threes attempted. Threes allowed –- and rim attempts allowed –- are also impacted by other categories, like:Fouling on defense

This year, the Knicks possessions end up in fouls 9.9% of the time, good for sixth-lowest.Last year, the Knicks possessions ended in fouls 11.7% of the time, tied for 10th-most.This year, the Knicks commit shooting fouls in halfcourt situations only 7.3% of the time, good for second in the league, and would probably be first if not for the Lakers and Lebron and their superwhistle.

Not bad for a team defined often by physicality!

That's a difference of merely a few free throw attempts, but freebies are invaluable. When looking at the entire portfolio of easy shots, we usually think about free throws, open threes and rim attempts. The Knicks haven’t monumentally transformed any one part of the portfolio, but they’ve really tightened up across the board. Perhaps the most remarkable improvement is how much more successful they are at ending possessions:Getting defensive rebounds

Last year, the Knicks DREB% was 72.7, good for 12th.This year, their DREB% is 75.8, first by a large margin. The Kings are secnd at 73.9%. Until the Suns game, the Knicks were even higher, closer to 77.

These Knicks simply have not been giving opponents second-chance opportunities. Those opportunities, as we know from New York's offense, often result in easy buckets at the rim and from distance. We can thank a full season of Josh Hart, minutes for the secretly-great-at-rebounding Donte DiVincenzo and Mitchell Robinson somehow going from a top-five board man in the league to the best are all contributing factors to our dominance.There is one final difference that jumped out when I was poking around Synergy and NBA.com:Forcing turnovers

Last year, the Knicks sucked at forcing turnovers: they were sixth-worst in the league, forcing turnovers on 11% of possessions.This year, the Knicks are tied for seventh-best, forcing turnovers on 13% of opponents possessions.

The combination of a conservative scheme by Thibs –- you hardly ever saw Knicks gamble for steals outside of Cam Reddish and later Hart -– and less athletic defenders up and down the roster meant the Knicks did not get many steals or deflections, and hardly any blocked shots. This year, despite a roster which is mainly the same outside of the Obi-Donte swap and Barrett in better shape, their defense is generating valuable turnovers far more than in prior years, for reasons we will explore.

So, despite worse rim protection, the Knicks seem to be locking in on defense. On the surface, beyond last year's defense being bad and this year's being good, there seems to be a lot different from not just last year but also from 2020-21, when we relied on rim protection, got minimal steals and allowed a shit-ton of threes.

Is there a relationship between the worse rim protection and better defense elsewhere? Is there anything schematically that has allowed us to force opponents into worse shot profiles? How much of this is Thibs versus how much is the players locking in? How much is sustainable and how much is small sample size? These are questions that require film more than stats. I looked mostly at footage from the Hawks game, but pulled from a few other games as well. PART II: THE VIDEO

What really got me thinking about the defense was the game against Atlanta. The Knicks had an uncharacteristically high number of turnovers leading to transition plays for the Hawks; shaky-shooting breakout forward Jalen Johnson hit all four of his 3-point attempts, a bunch of Hawks hit very tough contested jumpers . . . and they still scored TEN points under their season average. To be clear, the Hawks shot 54% from the field, 39% from 3 and took 26 free throws. So this wasn’t a good Knicks defensive game, but if that’s what a bad defensive game looks like, they’re in good shape. In that game, Mitch had his way on the glass, outrebounding the entire Hawks' front court. Additionally, Mitch and Hartenstein did not play tons of drop and therefore did not concede the Trae Young floater game. They alternated between aggressive pick-and-roll coverage and perfectly playing both the ball handler and the roll man. This was a new wrinkle for the Knicks after years of almost exlusively playing ''drop'' coverage, when the center backtracks after the opposing center sets a screen. The idea is to run a ball handler off the 3-point line and corral the opponent into midrange shots since the center dropping near the rim will be a deterrent to a rim shot. Thibs is known as a coach who really beleives that players — and a team — need to master basic actions and coverages before they learn new wrinkles. This is the first year he has introduced said new wrinkles on defense, so let’s get into some film and see why the defense has been so successful.Mitchell Robinson’s dominance

Mitch has been a great defender for a while, but he hasn't been quite the force on defense that guys like Adebayo, Joel Embiid, Rudy Gobert and Jaren Jackson are, to name a few. The reason? Those anchors pair physical gifts and top-notch timing with the know-how to bait and dictate to offensive players, rather than simply react to them.‘‘Playing two’’ usually refers to when a center in drop coverage gets into a little game of cat and mouse, trying to hide whether he is going to stick with an incoming ball handler or a center who might be an alley-oop threat. We already know Mitch is great at that, but what we haven’t seen as much is Mitch playing an aggressive coverage, and playing two in that situation. That is exactly what the clip above shows: he sticks with a top notch ball-handler, Dejounte Murray, leading Murray to believe that Clint Capela was open. Wrong. Mitch is in both places at once. That was hard enough for opponents when he primarily played drop coverage; now that he’s mixing it up, it is near impossible for opponents to read his pick-and-roll defense. This is the game within the game guys like Brook Lopez have mastered.

Watch Mitch in these four plays, two from the Hawks game and two from games after. Try putting yourself in the ball handler’s shoes in each. You know Mitch is primarily a drop coverage guy, and theoretically a bigger 7-footer. But you’ve heard the Knicks switch up their coverage now. Think about how that affects the ball handler’s decisions, whether it’s keeping a dribble alive, going for a floater, finding a passing lane, etc. It’s TOUGH out there for them.

On defensive plays categorized as ‘‘Pick and Roll Ballhandler’’ plays on Synergy, Robinson creates a turnover about 18% of the time and fouls under 5% of the time. I looked into all the best centers in the league, and literally none of them cause as many turnovers in PnR defense, and none foul as infrequently as Mitch. That gives you an indication of how his length, quick hands and — dare I say — veteran savvy let him juice the defense when he’s defending on the perimeter.

The best example I can think of regarding Mitch switching between ball-handler, then center, then defending without fouling, then getting the ball, was this play where he just totally erased Capela.

He doesn’t block as many shots as he used to, preferring to pick and choose his spots and cause turnovers via deflections and steals. More than that though, Mitch - and this entire Knicks team - has one singular goal for paint defense. To prevent a shot from going up, at all. That often requires staying your ground rather than going for a home-run block every time.

Coach Thibs embracing defensive scheme versatility

As I mentioned, the Knicks bigs are switching up their PnR coverage. This is almost certainly an intentional decision by Coach Thibs and the rest of the staff, and one that he deserves a TON of praise for. Zero fans/analysts/experts projected this team to be a good defense, despite having a few defensive-minded players. The Knicks mixing up coverages requires trust in not just Mitch and Hartenstein, but the rest of the team. We'll get into that shortly.

We've seen Mitch puppeteering offenses and dominating smaller ball handlers, so now let's look at Isaiah Hartenstein playing aggressively baits Jordan Poole into a pass he shouldn't make:I-Hart is, obviously, not on the same level as Mitch. He doesn’t quite instill the same level of doubt, preferring to just not play 2 and force the offense into a decision. But when he decides — or guesses — correctly, he can hang with ball-handlers pretty well for a true 7-footer.

But often he is actually guessing, or making a decision early and ‘‘selling out.’’ As a result, he’s often vulnerable to giving up open jumpers and even layups, like he does here to LaMelo Ball, who sees exactly what I-Hart has decided and exploits it.

The other thing that goes almost without saying is I-Hart can make hustle plays with the best of them, and having your backup center do this kind of stuff and close out playing 15 minutes straight against the Miami Heat is quite luxurious.

Robinson and Hartenstein. Two versatile centers, more than any pair of true 7-footers you’ll find on most any team. But utilizing that versatility was not an obviously smart move. I’ve talked for ages about how Thibs needs to experiment in the regular season, and this is why: you can discover game-changing evolutions for your plans. And now that Thibs has, I think he deserves lots of credit — both for building the foundation in Mitch and the experimentation in schemes utilizing his gifts (as well as other Knicks, as we will see).

More switching

The Knicks hardly switched last season, even when there were like-sized players running pick-and-rolls. This was one of the most common complaints about Thibs’ defense. It’s not rocket science, and plenty of teams switch like-sized players automatically. It was always an easy remedy for him to reach for, should he want it.

Letting the Knicks switch — especially Randle — is something that can selectively pay huge dividends. Bigger, more versatile guys like RJ, Julius, and Mitch switching challenges ballhandlers to attack players with quick feet who are bigger or reset and find another good shot, something that can take precious seconds off the clock and trigger mistakes and panic. It’s an underrated benefit of switching between similarly capable defenders, as the Knicks do here with Kawhi Leonard, of all people.

I still don’t think I would describe the Knicks as a switch-heavy team, but switching more than a couple times a game is a low bar that they had yet to clear under Thibs prior to this season.

Non-big rim protection

This. This right here is the special sauce. All of the stats, all of the other film of the bigs playing higher on the floor in aggressive coverages, all lead to this. To me, aside from Mitch, non-big rim protection is THE key to the Knicks’ surprisingly elite defense. Although there will be inevitable instances of bigger players scoring at the rim on their guards and wings, you’re conceding your opponent greater efficiency at the rim but allowing fewer attempts there and generating more turnovers. That is this year’s gamble in terms of defensive scheme, and so far it’s paid off due to the execution of the liliputians, as Clyde would say.

When Mitch or Hartenstein play more aggressively defending the pick-and-roll rather than dropping, the main rim protector is far from the paint It’s on the rest of the team to protect the rim, if not dissuade offenses from taking shots there. The Knicks don’t have the luxury of a rim-decimating monster-big wing like Giannis Antetokounmpo or Jaren Jackson or Evan Mobley lurking as the backup rim protector. We have Randle — not the greatest rim-deterrent in the world.

The Knicks have to rely on players 6-foot-3 to 6-foot-6. Unlike Randle, the guards are insane about deterring rim shots while rotating. They time rotations so that just as the ballhandler passes to the outlet/rolling player, a small Knick appears, allowing them enough room to land but hardly any to shoot or dribble comfortably. They each do it differently.

You’re familiar with how Brunson does it: charges! Watch how, as the big plays up, he waits and waits until just the right moment to slide in front of Capela, who is too goofy to dribble around JB. In doing so he abandons Wes Matthews in the corner, but watch how Donte DiVincenzo gets ready to swoop into Matthews’ passing lane if Capela was able to make the pass. For steal hawks like DDV, schemes like this that force opponents to pass more are a perfect fit for his off-ball defense skill set.

Even in this semi-transition below play, you see the same dynamic play out. It’s not quite a pick-and-roll, but Brunson sees De’Andre Hunter cutting and draws the charge, while DDV knows Mitch has Capela and knows where Trae’s next pass is. Even if Brunson didn’t get the charge, that’s probably a pick-six for Air Delaware. He is always hunting steals on and off-ball.

Speaking of the Big Ragu, here’s him in transition using his hops to protect the rim from 6-9 elite athlete Jalen Johnson successfully.

Depending on guards at the rim is something that applies just as much in transition at it does in the halfcourt. With Mitch, Julius, and Hart often hitting the glass, the Knicks are going to give up run-outs to the opposing team, and that puts a lot of pressure on the wings and guards to get back and defend the rim. The Knicks are among the league’s worst in frequency of transition plays allowed but among the best in transition points per possession allowed. Something to monitor going forward.

Speaking of Hart, here’s a play below against the Hawks where he tried his hand at being the low man defending a side pick-and-roll orchestrated by Bogdan Bogdanović and Onyeka Okongwu. Hart, like Brunson, times his rotation perfectly to tie up Okongwu. Tie-ups and drawn charges prevent the opponent from getting a shot off. Even a block comes after an attempt, and players do score over the outstretched arms of shot-blockers. But a charge? A jump ball? That reduces the chance of a shot going in to zero. That plays right into the Knicks take-more-field-goals modus operandi.

Even Julius gets in on the fun sometimes. Watch him wall up Hornet center Mark Williams using his strength — Williams can’t move Julius — allowing Mitch to return from LaMelo up top to swiftly take Williams’ cookies and start a fast break.

IQ gets his own section

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention the Knicks’ top rim-protecting small. Immanuel Quickley’s long arms, verticality technique, timing and off-ball foresight make him a genius as the low-man protecting the rim. Along with Mitch, he gives the Knicks a second elite defender.

Here, as the low-man, he stops PJ Washington long enough to let Hartenstein swoop back in for a steal. The same dynamic we saw from Julius and Mitch above. Whenever a Knick small holds the line, there is a very high chance a steal or deflection will follow if the ball is still in play.

Below, IQ isn’t the low-man in a pick-and-roll, but instead reacts on the fly from the opposite end of a court in a scramble situation.

Against the Wizards, IQ rotated to protect the rim from 6-foot-9 Kyle Kuzma after Fournier and Hart decided to double Corey Kispert (?!?!?).

On this play, IQ is beat on a well-timed and executed cut and immediately knows what will happen next; in a matter of nanoseconds he adjusts to become the low-man and — say it with me — protects the rim.

Elite off-ball defense is nothing new to Quickley, who’s supercharged the Knicks a few years on that end. When he’s in the game. the Knicks feel like they have six defenders. With IQ flying around shadowing players, when the rest of the Knicks hold the line defensively opponents struggle to find what should be the theoretically open man. That’s how you end up with late-in-the-shot-clock shots and turnovers.

The awkward Quentin Grimes section

Regarding Quentin Grimes, since I wrote several thousand words on the Knick defense without mentioning him once: his role remains the same. He takes on the toughest matchups, bar none. Elites and star ballhandlers are his burden to bear, one reason he isn’t tasked with the same kind of help defense as other Knicks. Grimes is typically guarding someone the Knicks specifically don’t want to leave open. He isn’t going to abandon LaMelo in the corner to help on a Mark Williams/Brandon Miller action. So far this season, those someones have torched Grimes.

Per Synergy, on plays Grimes defends the pick-and-roll ballhandler they’re shooting 57%. Last year it was 42%. This was something that I guessed via the eye test and confirmed via stats. A lot of that is small sample noise and will come absolutely back to Earth — guys like LaMelo and Anthony Edwards can torch anyone. It’s also been CJ McCollum, whose bodying of Grimes in the season’s opening week raised eyebrows. The book on Grimes is send a screen at him because his iso defense remains strong, while recovering from screens to impact the ballhandler has been tougher for him this year, not to mention he’s not the longest rearview-contest defender ever. His defense hasn’t been bad, but he hasn’t been the force we saw last year. Just another thing to monitor moving forward. If I were other teams, I would consider screening Grimes not with Mitch or Hartenstein’s man, but with Randle’s. Julius remains the one Knick you can rely on to not defend the pick-and-roll well. How New York handles those non-center screens for the All-Stars Grimes defends will be consequential, especially against better teams.

JR, RJ, JB: The weak links are stronger (well, two of ‘em)

If you had to summarize the Knicks defensive issues last season, you could do so in one sentence: three horrible defenders playing heavy minutes undermined whatever good defense the other two brought. By any metric, Randle, Barrett and Brunson’s defensive effort and execution were absolutely hopeless, and no matter how brilliant Mitch, IQ, Grimes, and Hart were, it is nigh impossible for a defense in this era of scoring efficiency records to remain structurally sound with that many weak points.

Brunson will always be in a tough situation one-on-one due to his size. The key for him is not missing rotations and dying on screens. Check this play out:

Brunson has been doing that all season. Instances of over-helping or not knowing where he needs to be are rarer than they were his first season in New York.

Barrett’s issue stemmed primarily from being out of shape (he hardly played two summers ago as he waited to sign his extension) and giving lackluster effort, and less from not knowing what to do. This year, after an excellent FIBA run with Team Canada, RJ is in fantastic shape and his individual defense has been solid — a level we haven’t seen since his second year.

He struggled getting around screens and impacting plays last year. While he’s still slow to recover sometimes after getting hit, he knows where he has to go, as seen here versus the Pelicans:

And Julius? Well, Julius is still pretty easily the worst defender on the roster. Where RJ and Brunson have improved their defensive fitness and technique and consistently put effort into rotations and closeouts, we too often see the same laziness from Randle we saw last year.

He will have spurts of attentive off-ball defense, and if he’s matched up with another big name he might lock in for a bit. Because there are few truly bad teams in the league now, my theory is most nights there’s someone for him to lock in on, at least a little. But he remains who he is on that end at that point. We’re talking years since he had any level of consistency on that end. Devin Booker’s game-winning three Sunday was illustrative:

The good news is a top defense can survive and remain pretty damn good with one bad defender, especially if that defender isn’t one you can just isolate on (Trae). So the Knicks have that going for them, at least.

The season is still young, and things like the Knicks allowing a lot of corner threes or transition attempts can still come back to bite them in the ass, especially if the collective effort lags at any point. However, the manner in which they do those things -- their transition vulnerability resulting from turnovers and not live rebounds, the threes they're allowing being highly contested, etc. -- gives me some peace of mind regarding sustainability. I think Thibs should be praised effusively for being more flexible on defense this year, and I think our litany of high-motor guys should be praised for leaning into what they are good at on defense -- Hart banging with power forwards, Brunson putting his body on the line, IQ covering for everyone else, DDV and Hart lurking behind every corner. Literally none of these guys will make an All-Defense team maybe outside of Mitch, yet all contribute to an elite defense, which is special and should be appreciated.Now if they could just get their offense in order, we’d be cooking!