What do the 2024 Knicks have that no Knick team’s had in 40+ years?

Hint: it starts with an “s”

Do you remember any of the monsters that scared you as a child? Was yours under the bed? Behind that one clearly sinister curtain or shadow? My childhood bed faced an attic that you accessed via sliding a pseudo-barn door. Because the door slid into place, in the dark it had the effect of seeming to disappear. When I’d sit up in bed and dare to peek toward the attic, it looked like a tunnel of darkness. I imagined all kinds of horrors in that tunnel.

Newly-verbal children often see things adults don’t. Clearly a lot of highly-educated adults have never watched horror movies, because a lot of them dismiss the childrens’ bizarre claims as developing brains failing to understand where imagination ends and reality exists. They don’t believe there ever is a monster in the closet, or attic. I suspect this has more to do with the limits of language and the license inherent in the non-verbal world, the one most of us turned our backs on 30+ years ago. If you can only recognize what you expect, what you have language for, what happens when the unexpected shows up at your door? Which brings us to the 2024 Knicks — by way of one last detour.

That’s the infamous clip of Patrick Ewing missing a finger-roll at the end of Game 7 of the 1995 Eastern semifinals. I saw it when it happened and have seen countless replays since. Yet somehow not until today did I notice something for the first time. And the reason I noticed it this time is because watching the 2024 Knicks has given me a new language, one that lets me recognize something I’ve never seen in a Knicks team before.

Ewing gets the ball with five seconds left. The defense is slightly aware he’s a threat.

He’s immediately doubled, but instead of passing out he spins and drives past the double. Note Charles Oakley in the corner when Ewing reaches the lane, and Derek Harper alone behind the arc.

Hindsight is 20/20; no Pacer fans in 1995 would have objected to the series coming down to Oak taking a long 2, and even with Harper having hurt them before no Knick scared them like Ewing. But after the Big Fella, Oak was those Knicks’ most consistent shooter from 15-18 feet, certainly a more reliable source of points for them that year than Ewing finger-rolls. Harper had already established himself as a big-game Knick. Behold Hubert Davis, who’d already come through in a big spot the year prior, getting fouled in the dying moments of Game 5 and hitting both free throws to give the Knicks a 3-2 series lead over the Bulls. Here Davis doesn’t even try to get open; he’s just a spectator, hoping the Knicks’ best player saves everybody’s bacon.

The point is not that the Knicks would have won if Ewing had dished to Oakley or Harper or Davis — Ewing would have been crucified for passing up the last shot, same as he was for missing it. The point is this sequence illustrates the reality the Knicks have lived in most of the last 40 years: in the biggest spots, when bucket-making is at a premium, they never have enough to go around. Two games into this year’s first round, it’s looking more and more like we may be living in a brave new world.

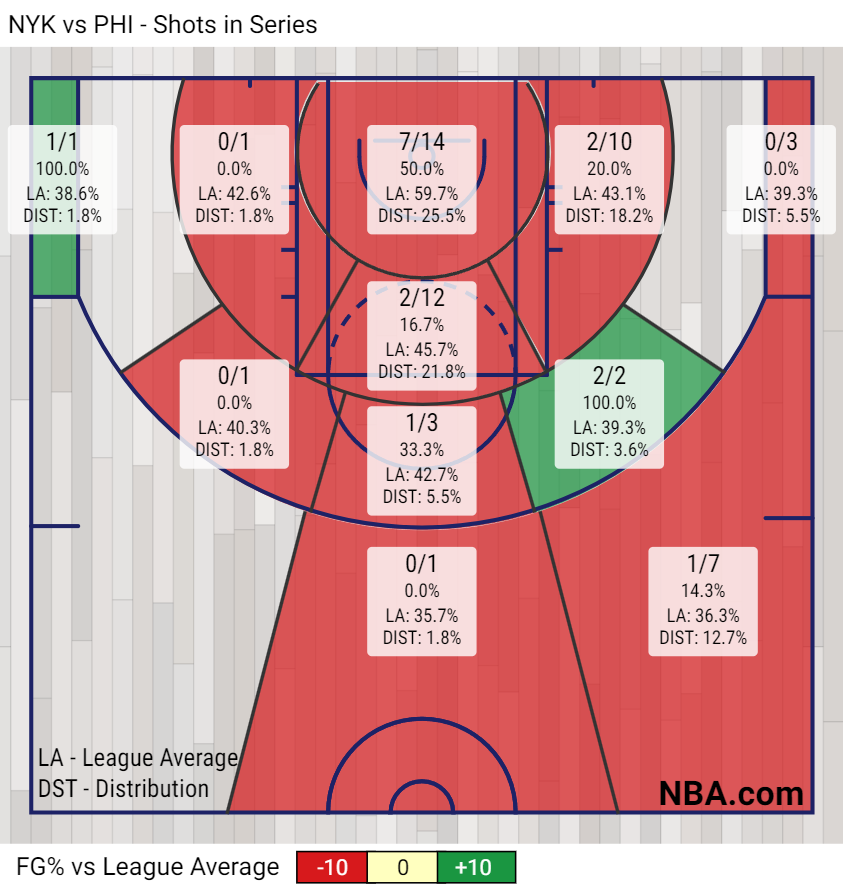

Jalen Brunson, you may have heard, has struggled with his shooting the first two games of the Knicks/76ers series. As you can see from his heat map.

The regular-season is a poor translation to work from when trying to get a read on the playoffs, like thinking Long Island can help you understand NYC because they border one another. The postseason is its own reality entirely, a place where your top-five MVP can look less like Peyton Manning than Elfrid Payton. So far Brunson has shot 4-of-14 defended by Joel Embiid, 2-for-11 guarded by Tyrese Maxey and missed all seven of his shots against Tobias Harris. Meanwhile, Embiid and Maxey are both averaging 30+, with the latter shooting a remarkable 54% from the field and 40% from deep. Anyone reading that a week ago would assume Philadelphia headed home looking to sweep the series. That New York is up 2-0 is testament to a truth that’s never been true in my lifetime: the Knicks’ supporting cast is title-caliber. Probably for the first time since 1973.

Consider the Bernard King era, the Ewing Silver Age and whatever MDMA fever dream the Carmelo Anthony run was. If you saw any of them, you know none of those teams were winning playoff games, much less series, if their leading scorer was in a funk. If King, Ewing or Anthony shot 30% the first two games of a series, their teams would be down 0-2. A deeper dive into their Knick playoff resumes illustrates the true spirit of those eras is reflected in what happened when their stars flickered. For our purposes, “good” shooting or shooting “well” means 50% or better; 33% or worse means “bad/poorly.” (all numbers courtesy of basketball-reference.com)

In 18 playoff games as Knick, the marvelous King only shot poorly once, in 1984’s Game 2 against Boston, which unsurprisingly New York lost by 14. In the other 17 games, he only shot below 47% once while making 60% or better seven times. When King shot well, the Knicks went 7-7. He had to go supernova just for them to have a chance. Luckily for them, he often did. That was King’s New York epitaph: brilliant but breathtakingly brief.

By contrast, Melo shot “poorly” in 7 of his 21 NY playoff games; in those games the Knicks went 1-6 and were blown out in half those Ls. The one win was a big one, though.

Melo shot “well” in only three of those 21 games, with the Knicks winning two of them. The one loss was a big one, though – eliminated by the Pacers in 2013. Meanwhile, in Ewing’s 135 postseason games as a Knick, he shot poorly 23 times, or 17% of them, versus shooting well 47% of the time. The Knicks were 11-12 in the former games, 36-28 in the latter. The takeaway from these numbers may tell us something about those players, but forensically their real significance is what they reveal about those teams.

In the 1983 Eastern semis, the penultimate Knicks/Sixers playoff matchup, half the non-King starters shot 40% or worse (Rory Sparrow, Paul Westphal). The only two other Knicks who shot well – Bill Cartwright and Trent Tucker – combined to score 18 points a game. The tragic irony of Ewing is the one time his Herculean feats lifted the Knicks within sight of Olympus, Derek Harper and John Starks (outside Game 1 and Game 7) stepped up, but it was the big man who had his worst-shooting series ever in the Finals. Even in the magical 2013 season, look at the Knick playoff shooting against Indiana. Jason Kidd took eight shots the entire six-game series and missed them all. J.R. Smith? 29% from the field. Iman Shumpert? 38% – and he was one of their hotter guards that series. Pablo Prigioni’s aim was fine, though he averaged fewer than three attempts a game. In retrospect, Raymond Felton’s 41% deserves a banner at MSG.

Things are different now. While Brunson’s struggled mightily against a Sixer defense keyed in on him, five of the other seven Knicks who’ve played are averaging double-figures – six if you round up Bojan Bogdanović’s 9.5 per game. Though Brunson’s made just two of his 12 3-pointers, the rest of the Knicks are shooting 44% beyond the arc.

In the decisive fourth quarter of Game 1, Josh Hart, Miles McBride, Mitchell Robinson and OG Anunoby combined for 27 of New York’s 32 points; Deuce and Hart both finished with 20+. In Game 2’s fourth quarter, 20 of the Knicks’ 25 points came from people not related to Rick Brunson. All five starters hit double-figures, with Hart again breaking 20 and Donte DiVincenzo netting 19, including this three you may have heard mention of.

The focus of this article is scoring, specifically, because the Knicks have always surrounded their great scorers with players who do other things. Truck Robinson was a rebounding fool. Anthony Mason was such a versatile defender he could shut down rush hour. Chandler was Defensive Player of the Year in New York. But when push comes to shove at the highest levels of competition, we’ve always been left wishing Ray Williams or Greg Anthony or Jason Kidd were the long-promised second star, be it Kevin McHale, Reggie Miller or a healthy Amar’e Stoudemire. Improbably it’s 2024, a year the Knicks lost their second star months before the playoffs, when they finally have a roster that combines to be more than the sum of its parts and our hopes. So much talk around this year’s Knicks has been pity that without Julius Randle, an otherwise credible title run doesn’t have enough gas in the tank. Maybe we missed the truth right under our noses. Maybe what we’re left with is all we’ve been waiting for.